What’s the music that got you into music?

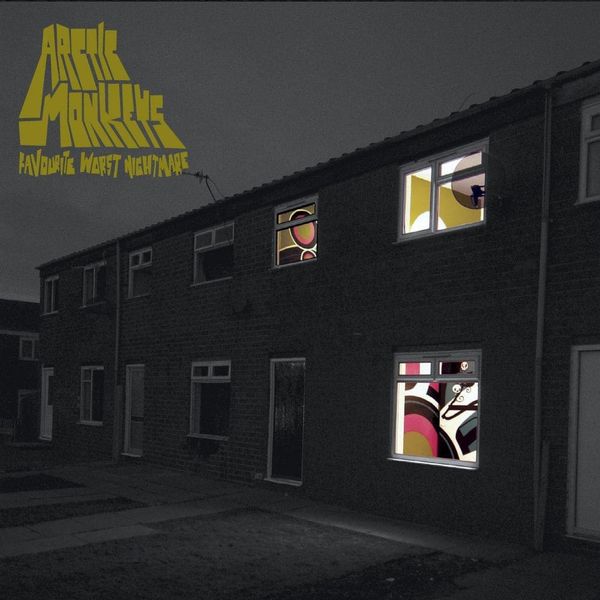

Well, I’ve always been surrounded by pop music because of my family. My mum’s side were really big on Motown and sing-a-long cheese acts like Daniel O’Donnell or The Monkees. I always used to sing to whatever was playing in my house often enough for me to remember. I met a guy in high school who knew how to play guitar and we had an acoustic duo together. At the same time I was finding music through my own avenues and through recommendations from friends. Arctic Monkeys were suddenly a big deal to me, so were Gorillaz. I think once I started discovering bands off my own back I always wanted to replicate what they were doing — I’ve always wanted to make music, but until I was maybe 13 or 14 I never had anything to accompany my voice.

What was it about groups like Arctic Monkeys and Gorillaz that clicked with you?

It’s hard to say with Gorillaz. Demon Days was the first album I ever bought with my own money so I’m not sure I had credentials for what I thought was ‘good’ back then. I just remember being so freaked out by the “Feel Good Inc.” and “DARE” videos when I was maybe ten-years-old, and I spent months trying to rehearse Booty Brown’s verse from “Dirty Harry”. I was late to the Arctic Monkeys party, though, and by late I mean I didn’t get into them seriously until I was maybe 17 or 18. By that point I’d been through an emo phase in the latter years of high school that I couldn’t quite shake off (and still haven’t because I’ve used a picture of me during that phase as the Moon artwork!). I’d become obsessed with British indie music in an attempt to re-brand myself for college. Joy Division, The Stone Roses, The Smiths… you know the types. Arctic Monkeys had four albums by this point and I was desperate to make sure they were the soundtrack to me cutting my hair short again and exchanging my brightly coloured hoodies for grey jumpers.

So I guess I’d like to put Moon in context a little bit. This is your third album. How did those influences lead into you first making your own music?

With hindsight, I think being into Arctic Monkeys and The Stone Roses just gave me enough street cred to approach other musicians in my area and start making music together. During my college years I was in a band with some other kids I knew through social media and being into ‘indie music’ kinda gave me a common footing with them. When I first started writing with them I wanted to be very public about how I’d moved on from my immature, old ways and had matured into someone who hated ‘cheesy trash bands’ like Paramore and My Chemical Romance. My love for emo pop was tied so closely to a relationship that was passionate and possessive and formative in ways that only teenage relationships can be, and I was reeling from the break-up for a long time. Looking back, though, it was my emo phase that had the biggest influence on how I wrote songs at that time — how I approached melodies as I constructed them, how I approached the subject matter in my lyrics, how I delivered it all once it was all put together. The music we made is still out there and you can hear all sorts of ’00s American pop rock in it. If Moon has come across how I expected it to, you’ll hear more Paramore and My Chemical Romance in there than you will Arctic Monkeys and Joy Division.

So you’ve kind of come full circle in that sense?

I could be wrong, but I’m sure there’s a passage by Roger Ebert that essentially implies that people always come back around to loving the stuff they loved when they were young after a brief period of moving away. I’ve been weak for pop music since my early childhood. No matter how far away I got, and no matter how much unconventional and ‘trendy’ music I love now, I’ll always came back around to the music that gives me the clear melodies and ‘verse-chorus-verse-chorus’ structure. Emo pop is my favourite blanket and I’m always comfortable its presence, and I always want to use it to express however I feel.

Am I right in thinking Colourful Sevens is a solo project? If so, what prompted you to leave the band dynamic behind?

It is a solo project, you’re right! Um, well, I was in a band during my first year of university in 2013 and I was really impressed with the songs we’d written. I was writing outside of my comfort zone but we played a live exam that went down a storm and we went back into rehearsals eager to make more. But then I got shouted at by another member over something I thought was pretty trivial — it wasn’t even ‘creative differences’, he just bollocked me in front of the other members for playing drums while he went to the loo. We had a couple more run-ins and I gave up. In the end, I said to myself, I don’t ever want to treat music so seriously that it causes me to argue with anybody — I’d rather just stay on my own, work at my own pace, and do my own thing.

Are there aspects of working in a group that you miss?

I miss the moment where somebody else would come up with a great riff or lead-in, and I’d find a vocal melody that connected with what they’d done, and for a second you’d share a look of excitement as though you’d struck oil. Beyond that, everything about working alone on music seems to trump the group setup.

Where did Colourful Sevens come from?

I had to put a blog together for a university assignment back when I was maybe 19 or 20 and I was struggling to think of a name. I was scrambling to find something, anything. In the end I stumbled across the name of an unreleased Boards of Canada song called “Infinite Lines of Colourful Sevens” and decided to split it in half. ‘Colourful Sevens’ rolled off my mind’s tongue better than ‘Infinite Lines’.

Agreed. You’re a Boards fan?

Music Has the Right to Children and *Geogaddi *are two of my favourite albums of all time and I have a tattoo of one of their logos on my forearm. I think I’d say I am, yes — haha.

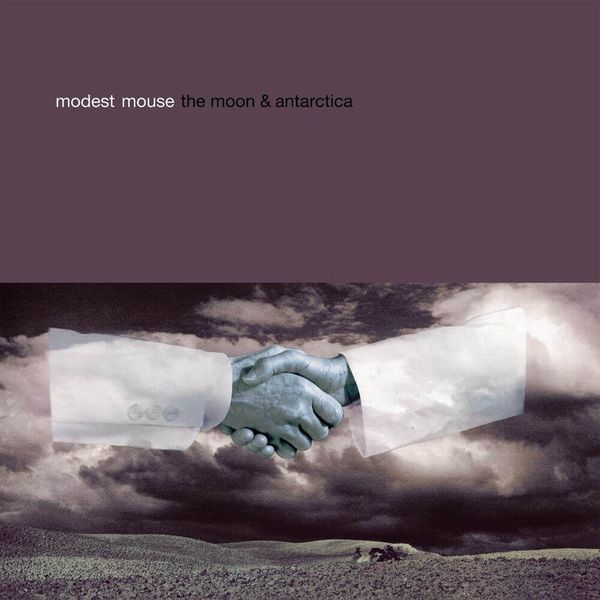

We’re big fans of Music Has the Right to Children. A similar ambient peace comes across in Moon’s softer moments

Yeah, I can’t afford to buy all the equipment necessary to sound like them so using all of Audacity’s crummy effects settings are the best option I have for emulating their sound!

So, Moon! It sounds like it was a bit of a return to home base for you then, so to speak. I take it the artwork kind of reflects that? What place has the record come from for you, overall?

Well, it’s funny, because as someone who has spent so much of his life consuming music, I always saw new albums as the beginning of a cycle. Now I’m used to working on albums for eighteen months and then finally releasing them, so I see new albums as the end of a cycle these days. The record itself is a semi-chronological, mostly autobiographical look at my emotional state between March 2017 and July 2018, so only certain sections of some songs apply to how I feel right now.

I think, listening back to Hem Haw OK, I’d reached a peaceful point in my life: I’d had health issues but was dealing with them, I was doing a masters degree, I was in a happy long-term relationship. But then that relationship ended quite suddenly, my masters degree came to an end, and my health issues stopped feeling so under control. Where Hem Haw OK looked out to the future with a hopeful glance, Moon covered my crash back down into reality.

The record starts in the immediate aftermath of that break-up, moves into analysing how the fuck I was supposed to cope with dating again with so much health anxiety, and then reaches the point where a new relationship starts just as I come to terms with change overall. Beginnings and endings and knowing the difference, as that Twin Peaks sample says on ‘Apr-1’.

So by the end you’d reached a beginning of sorts.

Well, when you get broken up with you try your hardest to form new habits to make it seem like you’re growing into a different person — even artificially. When I was 17 I threw myself into bands and cut my hair, and when I was 22 I threw myself into Twin Peaks. I had one song written by this point (“Ersatz”) which was just a bitter retort I put together while fretting over whether I could suddenly be friends with someone I’d been in love with for four years. Beyond that, Moon had no real structure. But then that episode came on, and that scene happened, and that line felt as though it had been written for me: ‘To beginnings and endings, and the wisdom to know the difference.’ Suddenly “Ersatz” was a step on a journey I felt compelled to cover.

Was the Twin Peaks motif there from the beginning or did it grow into the work later?

I tried to squeeze it into “Sleep” once that was finished but it didn’t fit, so in the end I decided to use it as a glorified introduction for “Ersatz”.

It sounds like the whole process was quite cathartic then.

I think that ties in to why I love making music by myself — I can treat my songs as diary entries. At the time of writing Moon I was falling deeply in love with Charly Bliss’ debut, Guppy. So much of Eva Hendricks’ lyrical content is confessional, sometimes embarrassingly so, and I was obsessed with capturing that myself. Not just singing about how the break-up had hurt me, but how my attempts to reckon with it had given me thoughts I’d be embarrassed to admit. How I’d suddenly started mythologising my ex, imagining her as an angel, and how it’d kept me up at night. How my chance to get over her was something that fell into my lap rather than something I’d worked for. How I’d tried to fill the space she’d left behind by reconnecting with friends I’d fallen out with years ago. Deep down we’re all pathetic and insecure, and being broken up with only makes that worse, and I knew I’d beat myself up if I didn’t put my fears down on paper.

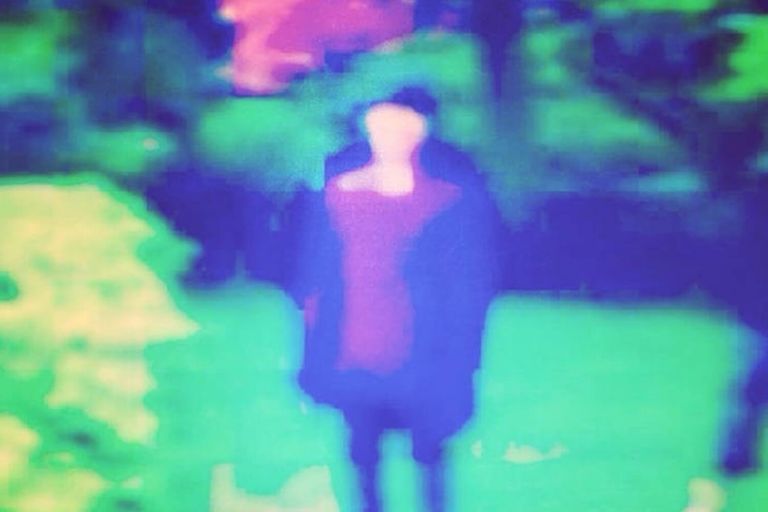

What’s the story behind the album artwork?

It’s a picture of me from when I was 16 or so. A friend of mine had a new camera so we decided to set a scene up at a park near his house. One of our group would kneel under a hedge while someone else would use them as a springboard to leap over it — we took several rapid-fire shots of people leaping over this small hedge. And in one of them, I’m just stood there, staring. All it did was remind me of that faceless family on the front of Music Has the Right to Children.

At the time I decided to use the image I was coming off that break-up and felt as though I was drifting and listless and lonely. I don’t know how I made the final product but I remember fucking about with photo filters until it was as distorted as it is now. I think my stance in that photo is one of someone who doesn’t want to be where they are. It applies to Moon‘s content, I hope.

I know it’s early days, but how do you think Moon sits in your discography?

I think it finds a queasy point between the first two albums and occupies a space there. It Does Not Matter was a nice idea but the entire thing was written, recorded and haphazardly constructed in the space of about three months. Looking back now, it shows. It’s an angry record. I don’t want to sit here and trash my own work but there are so many things about that album that I wish I could take back. It was before I started getting back in to emo pop and power pop and before I fell very deeply for early Weezer, so it was only on Hem Haw OK that I realised what I wanted out of life and used it as a place to let my anxieties play out. Moon feels like a realisation of both approaches, where I’m more aware of the direction I want to take an album in conceptually and focused on finding peace with my life, but reminding myself constantly that reality sucks in between its peaceful moments.

Are you writing anything new at the moment?

I’m always working on something or other. There are songs I wrote fully for Moon that, when it came down to it, didn’t really suit where Moon ended up going, so they’re hanging around waiting to be used. At the moment I’m back in my home town after living away from it for six years, so I’m at a point where I’m reflecting on how things have changed since I left. It’s strange to live in the same neighbourhood and to walk the same streets but for my points of access to be so different. I can see my old school building from my house but I wouldn’t be allowed through its gates, the park where I used to hang out in the summer is still there but other kids have taken my spot now. Writing new songs to fit to those ideas is another thing entirely — I have sketches but little more.

This is very much your project. Written by you, recorded by you, produced and mastered by you. You’ve compared the process to keeping a diary. What do you get out of that final step of sharing it with the world?

Honestly, when I was writing Moon, I imagined it being heard and understood by the people at the centre of its story, and that without having to interact with me directly, they become aware of how I feel towards them. Either that I’m sorry for anything I did wrong (“Sleep”), or that I understand why they made certain decisions (“Burn”), or that I love them very much and believe they’re very special (“Small Smile”). I see it as a way of talking to them without having to break the ice. I tried to end the album on a note that felt peaceful, much like Hem Haw OK did, but this time I wanted it to feel like I’d had to get through more to reach it. Yet, at the same time, telling person who caused the initial point of conflict — the break-up, being plunged back into the dating world as a sick person — that I didn’t hold anything against them because of how it all turned out. That if I had to force myself through heartache to find love again, or that if I had to learn how to live as a sick person in order to live properly as a well one, then it’s all worth it. In the end, it’s an album that tries to find the point where one cycle ends and another begins, and that it’s better to accept life as a series of doors closing hurtfully and unexpectedly so that hurt and unpredictability stings less every time. I suppose that’s a very long-winded way of saying that, essentially, you had to go through everything you’ve gone through to end up where you are.