Stewart Lee is a fat British comedian known for his unfunny routines and holding audiences in contempt. As a smug, pseudointellectual leftist, I naturally hold Stewart Lee in sycophantic high regard, to such an extent that I actually write a little bit like he does when I’m writing about him, though less articulately.*

I recently read Stewart’s book How I Escaped My Certain Fate, in one of the pages-long footnotes of which he lists his favourite albums of the 1980s: Handful of Earth by Dick Gaughan, Hex Enduction Hour by The Fall, Days of Wine and Roses by The Dream Syndicate, Pigs on Purpose by The Nightingales, and Prairie School Freakout by Eleventh Dream Day.

Naturally, I felt compelled to listen to all of them. Stewart Lee is quite possibly the only person on earth who looks back on the ’80s with any degree of affection, and it was clear this list held the key to why.

Beneath the decadence and depravity of those years, was there some god-honest filth worth liking? Had I, a 20-something liberal arts graduate with no cultural clout, been wrong to dismiss an entire decade out of hand? With Stewart, who will henceforth be referred to as Stewie, as my spiritual guide, I was ready to find out. Prepared for the worst, I set off.

Handful of Earth

Dick Gaughan (1981)

This kicked things off with unexpected dignity and tenderness. The ‘80s is typically (and rightfully) associated with ruin, but Handful of Earth is a purer animal than that. There’s a nobleness to Gaughan’s delivery that’s utterly disarming, the songs almost mythical in their simplicity and power. As Stewie puts it, ‘He’s one of those people who’s so good at folk guitar that it almost becomes avant garde.’ The Scotch should be proud.

Handful of Earth was made as a response to the Conservative Party sweeping to power in the 1979 election. Guaghan had a nervous breakdown and disappeared for a couple of years before returning to face down the Margaret Thatcher juggernaut with an abject defiance befitting socialists of the time (and since). ‘What seemed to be required was to openly stand up and be counted’, says Gaughan.

A period in Stewie’s career isn’t all that different. He dipped out of sight in the early 2000s, and it was only with his 2005 90s Comedian set that he really announced himself as ‘back.’ The set was itself a reaction against the religious right and its protestation of Jerry Springer: The Opera, a musical he co-wrote and directed and which had been sued for blasphemy.

The two’s journeys are not exactly the same. Gaughan’s dark night of the soul was a product of alcoholism and Margaret Thatcher, while Stewie’s had more to do with crisps and Jerry Springer; Gaughan stirs the soul with Highland ballads, while Stewie does it by vomiting into the gaping anus of Christ. These are minor points, though. There’s no point in splitting hairs.

Handful of Earth is clearly the origin of Stewie’s lifelong desire to be the Alternative Comedian, the insurgent flag bearer of values long since kicked to the curb. On reflection this makes sense as a starting point for Stewie. Any bitterness worth its salt is built atop the burial grounds of shattered dreams.

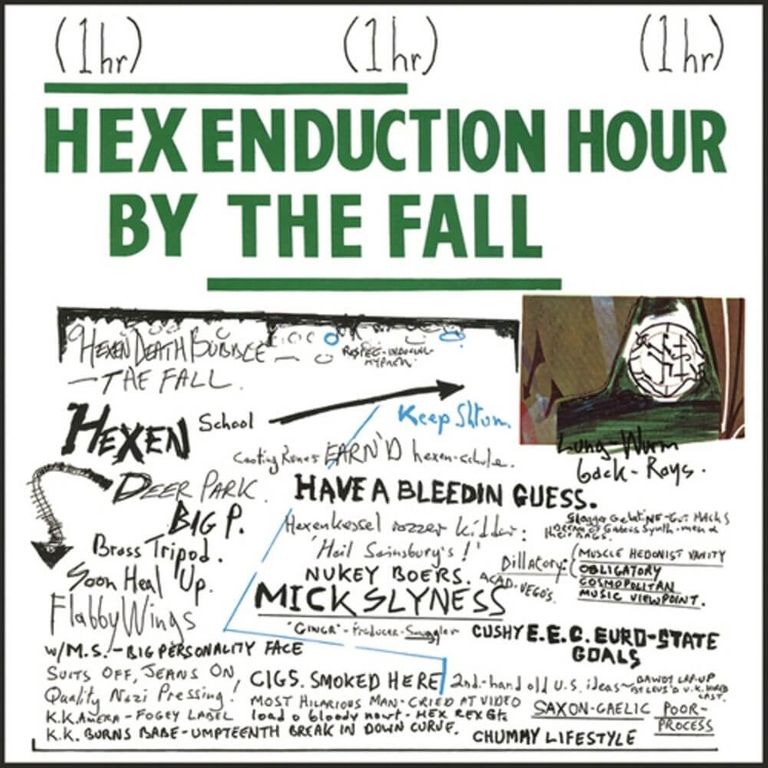

Hex Enduction Hour

The Fall (1982)

Stewart Lee’s career is largely The Fall’s fault. I’m not saying he’s Mark E. Smith’s illegitimate child. I’m not saying that. I’m saying Stewie saw ‘anti-comic’ Ted Chippington open for The Fall in 1984 and decided that was where his future lay. ‘It’s almost like a switch flipped. I’m sure it’s from listening to The Fall a lot.’ History turns on small, rusty hinges.

In any case, this, ‘probably the best album of all time’, was more like it. A rollicking mad journey through the underworld. We have previous with The Fall, having reviewed This Nation’s Saving Grace earlier this year. We dug its sleazy, delirious energy, and there’s plenty more of that knocking about in Hex Enduction Hour, which is indeed one hour long. It really is quite joyous in its blackened, miserable, lunatic way. It has an uncanny knack of making the world seem stupid and unnecessary — another Stewie linchpin.

Hex Enduction Hour is no great surprise as a choice for Stewie. He’s a faithful MES disciple. Remember when he was a thin, insufferable yob with an earring and floppy hair in the ‘90s? I can’t either, but there are YouTube videos of it. It happened. It was a proper post-punk vibe. The Fall inspired all manner of alternative artists, so it only makes sense for alternative comedians to be among them.

The record also drips with the rawness Stewie so clearly loves from music — and from art in general. Hex Enduction Hour revels in the frantic, inimitable energy of The Moment. “Iceland” is likely the best example of this, an impromptu jam performed only once and immortalised on record. As Stewie summarises:

Hex Enduction Hour is well worth a listen. The Fall are marvelous in their own right and it’s charming seeing Stewie trying to channel that energy into his cold, sterile, painstakingly rehearsed sets. They were nothing if not a take it or leave it band, and Stewie is nothing if not a take it or leave it comic.

MES and SL are kindred spirits here. Blackened, hateful spirits, but spirits all the same. Stewie once wrote (and maybe said, I don’t know) that, ‘Mark E Smith will continue regardless, with or without anyone’s approval.’ I would be deeply surprised if the same has not been thought countless times of Stewie’s comedy.

The Days of Wine and Roses

The Dream Syndicate (1982)

Moving on from the irredeemable farce of Stewie’s origin story, The Days of Wine and Roses glides in with sophistication and elegance. A lot of the same energies as Hex Enduction Hour are here, but the finish is slicker. This is extra impressive given the album was recorded and mixed in three consecutive night sessions, from midnight to 8am. It sounds phenomenal. The record channels post-punk, 2-tone, and other genres with names. It’s good fun with marvellous energy.

In a lot of ways Stewie’s sets are like records; they’re the same every time, but that doesn’t matter if the one time is good enough. Albums at their best are sublime moments captured in ember, and the same can arguably be said of stand up routines, though that would of course be ridiculous.

The Days of Wine and Roses is closer to the painstakingly crafted character Stewie brings to his shows in that there are elements of mess, but there is also tightness and professionalism, a nod to the constrictions of a format. To quote Stewcrates himself:

‘I’m not funny in real life. I thought of [a joke] when I got home and I wrote it on my desk and I learned it and I’ve come and I’ve said it to you tonight. And I’ve learned this, as well, that I’m saying now and written that. And this now, I’ve written that and learned that. And this, just going like that going like that, eurhhh I’ve learned that and I’ve written that and this now, I’ve learned this. And this, and this now and this. And just going eurhhh, I’ve written that and learned that. Everything’s written and learnt.’

The Dream Syndicate presumably practiced a lot to be ready to make The Moment count, and Stewie is no different. Even the most magical moments owe their existence to the graft that preceded them — and which follow as well. The Days of Wine and Roses is a quality flash of post-punk quality preserved in ember, a worthy precursor of Stewie’s work.

Pigs on Purpose

The Nightingales (1982)

Initially I didn’t think this was as good as the others. Having had time and repeat listens to think about it, I still don’t. Pigs on Purpose is yet another post-punk serving, and a decent one at that, with more of the faux-unfiltered, yobbish charm we know and tolerate.

Stewie claims, ‘In 1982, The Nightingales were the Birmingham Fall, and The Fall were the Manchester Nightingales, and it could have gone either way.’ Be this as it may, the production lets the album down. The trick of Hex Enduction Hour and The Days of Wine and Roses is their loose, frenetic energies are at the same time strangely immaculate, giving you the best of both worlds. Pigs on Purpose, however, sounds as you’d expect a low-cost post-punk band from the midlands to sound.

Pigs on Purpose is fine. Given that Stewie gets obvious, likely sexual satisfaction out of overdoing a good thing until its dead in the water, he probably threw this into his favourite albums of the ‘80s to prevent himself (or anyone else) from enjoying any of them too much.

Does it have the raw energy of Hex Enduction Hour? No. Does it bottle lightning like The Days of Wine and Roses? Not really. Is it an album by a Brummie band which likely holds some special sentimental value to Stew, who grew up nearby? Yes, and maybe. It’s not for me to say. I can’t read Stewie’s mind and his agent won’t answer my emails.

Prairie School Freakout

Eleventh Dream Day (1988)

This might be the best of them. It listens like a marvelous jam, which it basically was. Recorded ‘on a hot pollution alert day during July 1987 in Louisville, Kentucky … between 11pm and 5am,’ It seems appropriate that half that time was spent ‘trying to fix the wild buzz coming out of [guitarist] Rick’s amp.’ Prairie School Freakout is nothing if not a mad buzz. It’s relentlessly brilliant.

Stewie has a thing for spontaneity, and this caters to that nicely. Although his sets are laboriously scripted and refined over months, dashes of improvisation are one of his favourite aspects of performing. He doesn’t overdo it, because he isn’t funny in real life, but it’d unthinkable for Stewie not to dedicate parts of his acts to responding to the energies of the room.

The best thing about Prairie School Freakout is how effortless it feels. Three nights is impressive. One night is just silly. Everything comes together, happening because it can and why on earth not. There’s an ease to what goes, a confidence in what’s being made and why.

Stewie makes no bones about his fondness for the record, about how it mixes ‘the overdriven power of Neil Young’s Crazy Horse with the light-fingered finesse of Television and the iconoclastic energy of the American hardcore-punk.’ It’s hard to argue. Prairie School Freakout is a wild cocktail of creative energies served ice cold with a nice garnish.

In a strange, full-circle way, it mirrors the purity of Handful of Earth, and of Stewie’s more recent sets where he abandons traditional pretences and just yells at the audience. To abandon the rules is to master them. Eleventh Dream Day showed amp buzz can be its own theme. It is, as Stewie says, perfect, shabby glory.

Time’s passed, something happened

So there you have it. ‘80s music through the ears of Stewart Lee sounds like unjustifiably defiant leftism, upstart alternativism, and inimitable instances of beauty against the odds. Who’d have thought. It turns out he has an unironically good taste in music. Stewie still concedes that the ’80s ‘was a write-off really’, though, so my prejudices remain intact. Follow these albums and you’ll trace the spiritual journey of the most miserable man in comedy. Ground beneath the heel of The Man, Stewie rises again to not quite enthral us. I’m not saying he’s Jesus. That’s for you to think about, right.

* I have nothing to add here, but that never stopped Stewie. Why should it stop me?† ↩

† Rhetorical question. ↩