Context shapes conduct more than we often care to admit, and the same is true of art. In his 2012 book How Music Works, David Byrne writes that artists ‘unconsciously and instinctively make work to fit preexisting formats […] pictures are created that fit and look good on white walls in galleries just as music is written that sounds good either in a dance club or a symphony hall (but probably not in both).’ Similarly, music is often composed to compliment the format that will house it. While the focus of Byrne’s book is, on the whole, cultural, this piece is directed more at the influence format can have on the sounds it stores. To peek behind music’s curtain is to lay eyes upon a near-boundless world; that of circumstance. The meeting of woolly artistic intent and the stern, rigid realities of the world give birth to necessarily unique forms of beauty. Format influences form. At its best, it elevates it, and for an example one likely needn’t look further than a favourite LP.

Consider Pink Floyd’s The Dark Side of the Moon (1973). “The Great Gig in the Sky” (rumoured to have something to do with dying) closes out side one and the humble arc of life it paints: birth; panic and lost time; death. Wahay. In the record-flipping interval that follows—head swimming with visions of mortality and that thing you wish you had done differently and that other thing you wish you had done differently—a pseudo-existential crisis is raring to go. Have I missed the starting gun? I’m not a rabbit am I? Good god, what is certain in this life? Cha-ching. “Money” snatches you from the darkness and whisks you away into side two. The spiritual certainties of death are met with the material ones of cash and the trajectory of the album is altered, like light going through a prism. The album’s interval provides a pivot on which its character swings and renews its momentum.

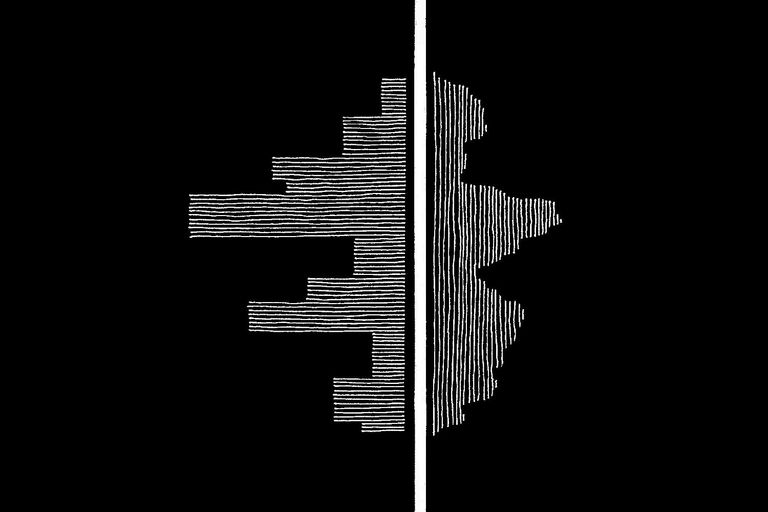

Alternatively, an album like David Bowie’s Low (1979) is characterised by sides that actively contrast with each other. ‘Fragments’ is a word that pops up often in reference to side one, a whirlwind of spunky glam rock snippets. Side two is anything but fragmented — an ‘Enofield,’ as Robert Christgau called it, a cotton cloud of synthesisers and Bowie moaning occasionally. In the mind’s eye, the halves look and feel completely distinct from each other, yet not to such an extent that one does not compliment the other. In the bells and whistles of side one, bordering on ironic in its briskness, is the performance; in the gentle and solemn reprieve of side two is an extended foray behind the eyes. It is hard to escape the feeling that Lowwould not be of the same calibre if its tone was uniform, if there wasn’t an exchange going on. The characters of a work’s two (or more) sides combined can sometimes amount to more than the sum of their parts. In both *TDSotM *and Low, the LP’s sides are not the lynchpins of their quality, but they are undoubtedly part of the recipe. Format prompts adaptation, a process that can provide as many creative tools as it deprives.

Vinyl is not unique in this respect, it is just provides cushy examples of works adopting their format to their own ends. Although music’s majesty often comes from its ethereal, untouchable quality, it bears remembering that—at least where recorded content is concerned—the listener is effectively faced with a ghost in a machine. Brian Eno, in a lecture written in late 1970s entitled ‘The Studio As Compositional Tool’, stated that recording ‘takes music out of the time dimension and puts it in into the space dimension,’ giving it permanence and form. He goes on to say that, ‘Once you become familiar with studio facilities, or even if you’re not, actually, you can begin to compose in relation to those facilities.’ Circumstance prompts unconscious and instinctive adaptation. For Bryne this is true of performance, for Eno of the recording process, and so too is it true of the format being recorded onto.

Album sides are a prime example of format affecting how music is built and how it is received. Constraints invite adaptation. The simple reality of the LP record format—two sides at typically 20-25 minutes each—sparked creative instincts that shaped many of the albums produced during the format’s dominance. When we talk about album sides, we don’t do so in purely descriptive terms. They often carry a thematic weight or allow for narrative ‘beats,’ like acts in a play or halves in a film divided by an intermission. The interlude provided by the necessity of flipping a vinyl album over gave artists a circumstance to play with. It is from such practicalities that unique forms of beauty can blossom. This is not to say it will, or that works which do not ‘use’ their format are lesser than ones which do, only that it is an dynamic of recorded music worth considering and keeping an eye out for.

Circumstances are changing all the time. Cassettes, CDs, digital audio files, streaming services—all are beholden to their own freedoms and constraints that influence how the music they store is created, recorded, shared, and experienced. Take digitally distributed music, for instance. In an era characterised by playlists and unprecedented access to individual tracks, it makes sense for the form of recorded sound to react accordingly. Contemporary albums often appear more like an unrelated cluster of shards—as if side one of Low has been blown to pieces—than they do a complete, multi-faceted big picture. Songs have to be potent in their own right to be a worthy purchase in their own right, after all. The juxtaposition between streaming charts and physical/vinyl charts are telling in this regard.

Are such trends a bad thing? Not necessarily. Gorillaz’s eclectic odyssey Demon Days (2005) is a magnificent example of a CD album, while Joanna Newsom’s very gorgeous Divers (2015) makes more sense—at least to me —as some kind of eternal digital loop. Parameters change and, teething problems or not, that is ultimately an exciting thing. Something unprecedented will eventually step into the new frontier. As David Byrne notes, with the constraints of older formats cast aside, artists ‘could make a downloadable album that’s ten hours long, or ones that only last ten minutes.’ Or, elsewhere, we might see some trends come full circle, with playlists inheriting the cassette mixtape’s old aura (‘audio wonder cabinets’ as Byrne describes them), with tracks groomed to vie for positions on personalised ‘albums.’

Although I personally find declarations that ‘the album is dead’ more than a little overdramatic, there is a value in looking at the shifts in format and distribution that inform them. With more musical mediums and technologies co-existing than ever before, there is enormous potential for works to blossom in unprecedented ways. Tentative steps are already been taken. Radiohead’s audiovisual app PolyFuana marks a colourful experiment in the potential of modern music-playing devices, while Brian Eno, ever pushing the envelope, has accompanied the announcement of his upcoming album The Ship with threats to develop ‘multi-channel 3-dimensional sound installations.’ And these are modest examples; things will get stranger.

Plenty — I included—will continue to be delighted by what is familiar, but it’s only a matter of time before certain artists start dabbling in what will initially seem like spectacularly weird ideas. There’s too much at stake not to. Raw and rich forms of beauty await those willing to immerse themselves entirely in the cold and alien circumstances of their time. There are expressions to be made that were not possible even ten years ago. What they are I don’t know, but I await them eagerly.